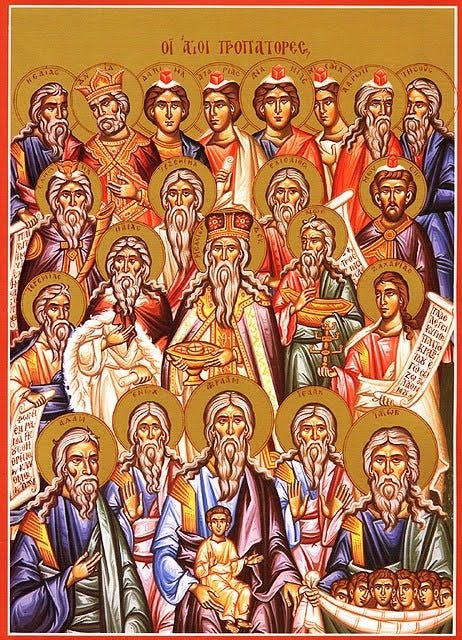

The Church Fathers (source)

***

Consider the following argument:

If the Church Fathers universally regarded a given action as seriously immoral, then Christians have strong prima facie reason to regard that action as seriously immoral.

The Church Fathers universally regarded abortion (at any stage of pregnancy) as seriously immoral.

So, Christians have strong prima facie reason to regard abortion (at any stage of pregnancy) as seriously immoral.

Let us call this the Patristic argument against abortion.

Premise (1) will be accepted by any Christian who affords significant epistemic weight to the Patristic tradition. This will include Catholics, Orthodox Christians, high-church Protestants (e.g. Lutherans, many Anglicans), and some low-church Protestants. The motivation behind the premise is simple: Christians believe that Christ founded the church in order to preserve and promulgate his teachings, and that he promised it guidance from the Holy Spirit. As such, we ought to trust the universal consensus of the church’s leading theologians. Furthermore, a universal consensus among the Fathers (particularly the early Fathers) is strongly indicative of a given teaching’s apostolic origin. This should give it significant weight even with low-church Protestants, for even they generally grant that the apostles themselves taught infallibly (or at least authoritatively) on matters of faith and morals.

Premise (2) is simply a historical fact, which can be easily verified by an examination of the Patristic sources.1

A common objection to this argument goes as follows: the Fathers were not infallible, and indeed there are some moral issues (such as the in-principle permissibility of slavery) where they are generally agreed to have been seriously mistaken. The church has morally developed over time, and we should not be beholden to the moral views of the earliest Christians.

How should one sympathetic to the Patristic argument reply to this objection? I think the right response will focus on the character of the church’s moral development. Specifically, there has been an increasing appreciation of human dignity, which has led the church to recognize the immorality of slavery, the persecution of heretics, the legal punishment of sexual minorities, and various other violent acts. Furthermore, there has been an increasing recognition of human equality: whereas in the past many Christians embraced racist or sexist views,2 today such positions are generally recognized as seriously wrong.

Now, notice that for the pro-choicer’s objection to the Patristic argument to succeed, they have to propose a very different sort of moral development: they must contend that the Fathers overestimated the value of human embryos, that here they believed too much in human equality, that in this case their moral circle was too wide. The modern pro-choicer is said to be the one who has uncovered this error, overturning two millennia of excessive humanism on the part of the church. This is strikingly out-of-step with the general trend of Christian moral development.

Furthermore, notice that the errant moral views held by the early Christians were typically shared with non-Christians. The in-principle permissibility of slavery was not an idea original to the Fathers: it was simply assumed in the societies where the Fathers lived. The problem was precisely their failure to challenge the moral consensus of their culture. Similar things can be said about ethnic prejudice, sexism, and so on. By contrast, the moral innovations introduced by the church (e.g. the emphasis on care for the poor, the fervent rejection of child sex abuse, etc.) constituted genuine advances.3 Importantly, this is what one would expect if Christianity is the true religion: if the church is guided by the Holy Spirit, then it is hard to see why it would be introducing genuinely new moral ideas which turned out to be seriously in error.

If this is correct, then we have very good reason to believe that the Patristic prohibition of abortion is correct. As Alexander Pruss writes:

The early Christian tradition rejected abortion, often as a crime on par with infanticide. For instance, the second-century Didache4 commands: “thou shalt not kill a child by means of abortion, nor slay it after it has been born [ou phoneuseis teknon en phthora(i), oude gennêthen apokteneis].” Interestingly, all this was while leading philosophical theories (e.g., those of Aristotle), together with rabbinical Judaism, insisted that the embryo/fetus has no soul either during pregnancy as a whole or at least during the first weeks after conception. The apparent classification of abortion as a sin on par with infanticide, despite the surrounding intellectual and practical culture, makes it likely, given the way the Holy Spirit guides the Christian community in truth (John 16:13; cf. 1 Tim. 3:15), that the Christian prohibition on abortion did not derive from sources other than divine revelation. (2012, 188-189)

This comports with our earlier note concerning the likely apostolic origin of universally-held Patristic teachings. The pro-choice objector to the Patristic argument has to hold that in this case, the church introduced a false moral view against a pagan and Jewish world which already had the truth. This is very surprising, at least given any plausible view of the relationship between God and the Church.

The upshot is that the Patristic witness gives Christians a very strong reason to regard all abortion as seriously immoral, a reason which is not defeated by the facts concerning the church’s moral development.

See e.g. Jones, The Soul of the Embryo: An Enquiry Into the Status of the Human Embryo in the Christian Tradition (2004), New York: Continuum. Jones notes that “The earliest Christian texts placed ensoulment at conception” (123), with the delayed ensoulment view only becoming prominent after several centuries. Even then, “[it] was much less prevalent in the East and it is not unquestioned in the West” (123), with theologians such as Gregory of Nyssa and Maximos the Confessor continuing to argue quite explicitly for immediate ensoulment. Eventually, as embryology developed and theologians became increasingly willing to question the authority of Aristotle, the immediate ensoulment view became dominant in the West once more. It is also worth noting that even those Christians who embraced a delayed ensoulment view continued to regard abortion as a mortal sin. For a modern pro-life view which accepts delayed ensoulment, see Swinburne, Revelation: From Metaphor to Analogy (2007), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

This includes even otherwise-brilliant theologians: see e.g. den Dulk, “Origen of Alexandria and the History of Racism as a Theological Problem,” The Journal of Theological Studies 71 (2020): 164-195.

For a popular treatment of this issue, see Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (2019), New York: Basic Books. For a scholarly examination of the ways in which the early Christians differed morally from their peers, see Hurtado, Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World (2017), Waco: Baylor University Press.

Despite Pruss’ reference to the “second-century Didache,” many scholars date that particular text to some time in the first-century. This makes it even more probable that the book’s unequivocal condemnation of abortion reflects genuine apostolic teaching. For a summary of recent work on the Didache, see Wilhite, “Thirty-Five Years Later: A Summary of Didache Scholarship Since 1983,” Currents in Biblical Research 17 (2019): 266-305.

If someone is strongly Pro-Choice (i.e. has a high credence in that view) would you say that the considerations here should lead them to lower the total probability of Christianity being true as a whole given its endorsement of the Pro-Life position historically and presently?

I think this point--"if the church is guided by the Holy Spirit, then it is hard to see why it would be introducing genuinely new moral ideas which turned out to be seriously in error"--is extremely insightful.

But I have an example of a Christian moral teaching that was both genuinely new and seriously in error. One which goes back to Jesus himself, and was unanimously embraced by Patristic authorities--*more* unanimously than the acceptance of slavery, where Gregory of Nyssa heroically dissented.

I'm referring to the absolute ban on divorce, save for adultery--and, very significantly, with no similar exception for abuse.

I'm aware that contemporary apostolic Christianity, Orthodox and Catholic alike, has softened this stance in practice. Orthodoxy started recognizing abuse as a grounds for divorce in the 20th century (in Russia, canon law was changed in 1916). Catholicism started recognizing abuse as a grounds for separation in the High Middle Ages (c.1300). But the actual Patristic sources are unanimous in decreeing that a woman violently abused by her husband must remain with him and endure it--she sins by leaving even if she doesn't remarry. Basil the Great spells this out in his canonical letter on legitimate grounds for divorce: if a battered wife who "cannot bear the blows" leaves her husband, she's guilty of culpable abandonment.

And this was, seemingly, *the* most genuinely unique Christian moral teaching in its cultural context. There were pagan Greco-Roman philosophers who denounced infanticide, abortion, child abandonment (Musonius Rufus), male infidelity, pederasty, forced prostitution (Dio Chrysostom), and non-reproductive sex--but not a single one who morally condemned divorce. Roman law, famously, allowed either spouse to initiate divorce for any reason--until Constantine and his successors ended this. Note, in particular, that while the earlier, compromising, Theodosian Code left serious physical abuse as a permitted grounds for divorce, Justinian's revision eliminated that escape, thus bringing secular law in line with Church doctrine.

And, on the Jewish side, while the Torah grants only the husband the right to initiate divorce, Second Temple Judaism--including in Palestine--seems *in practice* to have allowed women to initiate as well, as shown by preserved legal papyri. Already in the Mishnah, the idea that wives have the right to divorce is their husband is in some way unbearable has developed, drawing on the stipulation in Exodus 21 about the things a wife has a right to expect from her husband, and in medieval Judaism this evolved into a right (and even a duty) to divorce in case of physical abuse.

This seems like an underdiscussed weighty piece of evidence against the truth of Christianity--that *the* most distinctive new Christian moral teaching was seriously enough in error that no current church maintains it in its old rigor.