***

Introduction

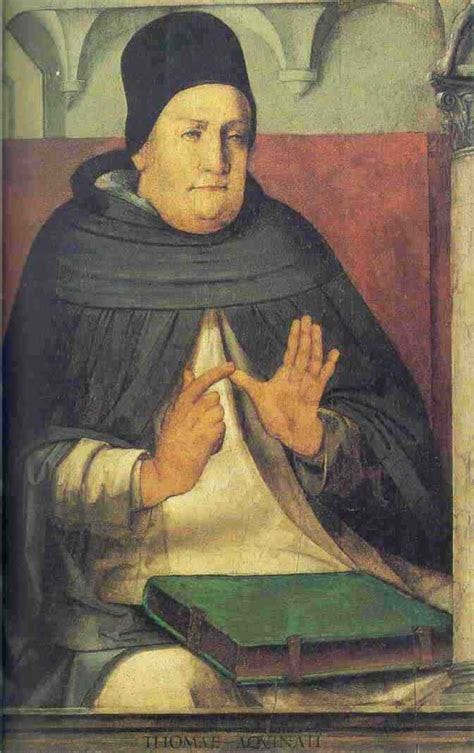

Aquinas’ five ways are among the most widely-discussed arguments in all of philosophy. That being the case, it is no surprise that they have been interpreted in a multitude of different ways, each of which have been developed, critiqued, and explored in remarkable depth.

My goal in this post is to defend a currently under-appreciated reading of the five ways—or the first three, at any rate—which I call the “aggregative approach.” This interpretation of the arguments has been defended by such influential Thomistic philosophers as Peter Geach (1961), John Lamont (1995), and Christopher Martin (1997). Despite its impressive pedigree, however, the aggregative approach is little talked-about today,1 a situation which I hope to help rectify.

Sketching the Aggregative Approach

The basic idea behind the aggregative approach is simple. First, we identify a particular feature of the world, each instance of which requires a cause. Second, we appeal to an aggregative causal principle (ACP) of the form “if every member of a plurality has a cause, then the whole plurality has a joint cause.”2 From these first two steps, we conclude that the whole plurality of instances of the relevant feature has a cause. Finally, we draw out some implications concerning the attributes of this cause. The basic argument schema may be laid out like so:

If every member of a plurality has a cause, then the whole plurality has a joint cause.

Every X has a cause.

So, the whole plurality of Xs has a joint cause.

If the whole plurality of Xs has a joint cause, then there is an F.

So, there is an F.

In the first way, we substitute “instance of change” for X, and “unchanged cause of change” for F. In the second way, we substitute “caused substance” for X, and “uncaused cause” for F. In the third way, we substitute “contingent substance” for X, and “causally-efficacious necessary being” for F.

This reading of the five ways has an important advantage over its competitors, namely that it requires many fewer controversial assumptions: in particular, the aggregative approach does not require the denial of existential inertia nor the necessary finitude of per se causal chains.

Motivating the Premises

Why accept the premises of the aggregative five ways? Let’s examine each in turn.

Premise (1) (i.e. the ACP itself) seems fairly intuitive; indeed, similar principles are defended by a number of authors. For instance, Josh Rasmussen defends the “principle of dependence,” according to which “Totals of dependent things are, by nature, dependent” (2023, 4). The motivation for this principle is that “dependent things cannot, just on their own, add up to some independent total” (ibid., 4). Similarly, W. Norris Clarke writes that “if all the beings in [a causal] chain remain conditioned, dependent on another, then nowhere will the conditions for the existence of any member ever be adequately fulfilled… the entire chain [will remain] suspended without a sufficient reason, or adequate grounding, for any of them to exist” (2001, 217).

Premise (2) will obviously differ depending on which way we are examining; however, each version is highly defensible. In the case of the first way, the claim that “every instance of change has a cause” follows from the Aristotelian metaphysic accepted by Aquinas. In the second way, we have “every caused substance has a cause,” which is basically a tautology. In the third way, we have “every contingent substance has a cause,” which is very plausible, and widely-accepted amongst philosophers of religion (including some atheists). In each case, I think the relevant principle is very probably true: instances of change, caused substances, and contingent substances are all plausible (in the second case, tautological) candidates for things which require causes.

Premise (4) will also differ a bit depending on which way we are talking about. Assuming that the joint cause of a plurality must not involve any members of that plurality,3 we can say a few things about the being arrived at by each of Aquinas’ arguments: in the first way, we arrive at a being which causes change without itself undergoing any change (i.e. an “unchanged changer” or “unmoved mover”). In the second way, we arrive at an uncaused cause of all caused substances. In the third way, we get a non-contingent (i.e. necessary) being.

Conclusion

The aggregative approach enables us to run Aquinas’ cosmological arguments without any problematic appeal to persistence, the denial of existential inertia, or per se causal chains. It requires for its success only a few (highly plausible) causal principles, as well as the claim that causes cannot overlap their effects. All-in-all, I think we have here some likely-successful pieces of natural theology.

The only critical engagement with the aggregative approach which comes to mind is Côté’s (1997) remarkably weak reply to Lamont’s defense of the arguments.

This is a slightly modified version of the aggregative PSR employed by Koons (2023). By F’s being a joint cause of plurality P, we mean that for every X such that X is a member of P, F is causally prior to X. This assumes (as is plausible, though not entirely uncontroversial) that causation is transitive. For more on this topic, see Pruss (1998) and Koons and Pruss (2021).

Doesn't this basically shift all the five ways into a Leibnizian-De-Ente style argument?

This nicely gets to the core of the arguments, as well as the heart of my worries. I am quite convinced that (at least most of) the aggregates mentioned above are subject to set-theoretical paradoxes and I don’t know if this can be resolved by plural quantification. I would love to be able to endorse these arguments though